Gio and Her Dissident Act of Self Love

Once upon a time, a little girl dreamed of being like JonBenét Ramsey because all she heard was that blue-eyed blondies were prettier and had better lives. She carried a notebook everywhere she went and wrote poems and love songs that got her in trouble with her parents because they feared she had a noviecito. She also loved to draw.

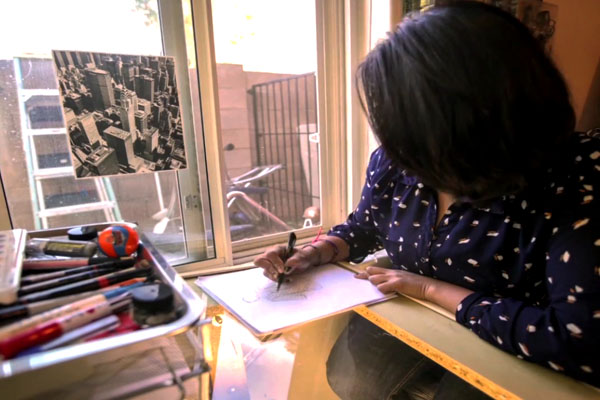

Gio creating on the drawing table her dad made for her. Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

She had wacky ideas since she was little. One day, while playing with her cousins on the street she lived on in San Francisco Culhuacán in Mexico City, she decided it was a good idea to open the gas tank of a parked car and take a peek inside. She thought she had seen the whole universe, a set of celestial bodies dancing in the cosmos when she did it. There’s a chance the petrol fumes had something to do with it, but she felt the entire world could listen if she sang, projecting her voice inside the gas tank. Freaky, right? She was given the name Giovana, and she was so obstinate that one night, after going to the movies with her parents and watching Marcelino Pan y Vino, she made the local priest open the church in the middle of the night to ask God a few questions…so Jesse Custer.

She grew up loathing the skin color that covered her inner beauty, carrying an inferiority complex for displaying an Indigenous phenotype and listening to Leo Dan, The Beatles, Zep, and other rock bands because her dad was a headbanger.

Most of her designs are made with recycled materials. Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

Gio didn’t have it easy (that doesn’t make her unique; how she used her struggle does). Her dad migrated to the U.S. when she was 6 years old in search of opportunities. Three months later, Gio, her younger brother, and preggers mom crossed the border through Nogales. The van that transported them dropped them off at the Circle K on 7th St. and McDowell (now a Chase Bank branch).

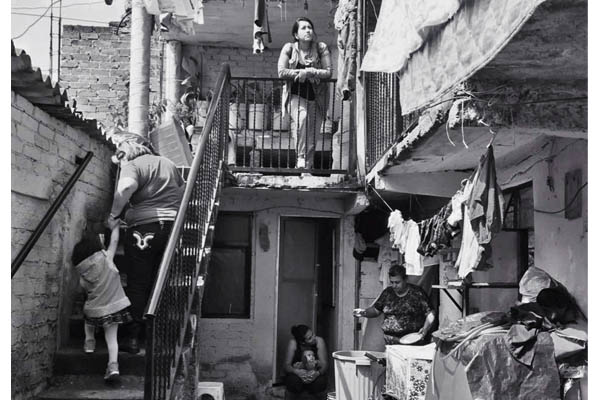

Visiting the home she grew up in on her first visit after a few decades. Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

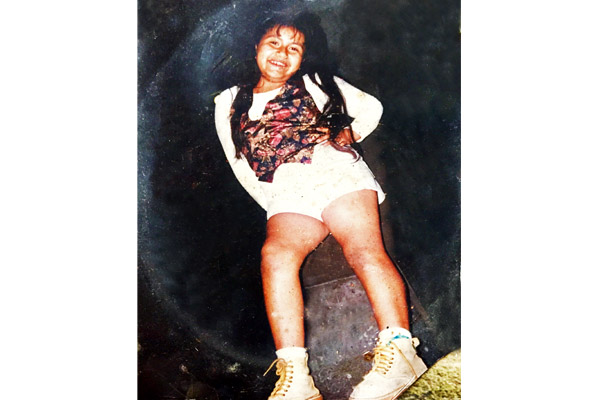

Initially, she imitated her cousins when speaking English, and her classmates at Emerson Elementary bullied her because she mispronounced words or was developing quicker than the rest. Also, because her dad made her wear some crazy-patterned vests that she hated, her dad made sure to get them the flyest Nikes.

He was very fashionable, hence the vests, booties, and hats, but sometimes, Gio refused to wear what she was told and hid her things. However, she learned to match her outfits and choose the shoes (and vests) she liked.

¿How ’bout that vest? Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

When she was in 8th grade—and her parents could finally afford cable—she discovered The Fashion Channel. At that moment, she realized that fashion interested her the most. She wanted to get involved in runway shows and be like Gianni Versace.

As if it were church, Gio religiously waited for Sundays to watch a fashion show on TV and learn the process of putting up a show. She would take notes and dream of doing it like she did on TV.

Around that age, she also had her first disappointment when she couldn’t participate in the Hispanic Mother and Daughter from ASU because she didn’t have a Social Security number.

She always knew she was undocumented in a way. One day, many years ago, when she was at a hacked payphone that allowed her to talk to her family in Mexico for longer with very little money, she heard someone yell, “La Migra,” and her family started running. Gio didn’t understand why they were doing it, but she learned she had to run when she heard those words.

But with the same gutsiness that she insisted the priest open the church in the middle of the night, Gio looked for ways to train. In her senior year of high school (she went to North), she was part of the design program at Metro Tech. Thanks to that program and the people involved, she found herself; she stopped feeling embarrassed and like an outcast.

She kept at it and, after graduating, started taking fashion design classes at Phoenix College, although she considered them crappy. Like many of her friends, her path was interrupted when Prop 300 was passed, increasing tuition costs for undocumented students. She said fuck it to all that noise and started working with DREAM Act and DACA activists.

Gio is doing what she knows best: resisting! Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

She used art as a catharsis for her frustrations after combating a system besotted on making her life (and that of many of her friends) miserable. She participated in plays and kept writing and drawing.

She also helped with her family’s expenses by working various jobs, from housekeeping at a resort to a teller at a title loan joint. Even though she wasn’t eligible to work, she landed a job at Macy’s, which didn’t last long because they found out about her status.

After a while, a friend teaching a modeling class asked Gio if she could create outfits made of recycled materials. Gio took up the challenge and impressed herself with the results. Shortly after that, she was invited to participate as a designer in a fashion show for the Stylos Awards, a cultural event showcasing local talent. This opened many doors for her, and in 2013, she had her first solo exhibit at ALAC (Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center).

First solo show at ALAC (Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center) in 2013. Photo: Courtesy Giovana Aviles.

Gio isn’t bothered by the color of her skin anymore. She stopped questioning its shade. She discovered that self-love is a dissident act and that this was more than just Twitter knowledge. Thanks to the example of women of color like Selena and J-Lo, to a degree, she learned to love her body, the lines that shape it, and the beauty with which her ancestry is reflected in her features. Because of this, she decided to participate in a collective exhibit with other Latina artists at The Sagrado Gallery in South Phoenix. She feels that by sharing her story, other women can change their perceptions of their bodies and who they are; that if she shares her struggles and how she overcame them, other women and little girls will know that they can also achieve this.

You better not miss it!

Gio doesn’t want to be the blondie that Leo Dan sings to; she doesn’t want to be slimmer or adhere to media beauty standards. She is tired of people appropriating the stories of people of color and telling them as their own; she believes that POC should tell their own stories so that others don’t do it for them.

Gio and Betsabeé Romero at the reception for an art collaboration with other Phoenikerx artists. Photo: Alonso Parra/Lamp Left Media.

Her struggles shaped her; without them, there would be no Gio. What once was a source of pain and struggle is now her strength.

The little girl who once thought the whole world could listen if she sang into a gas tank is being heard. She would also like other voices to be heard and for more local artists to occupy spaces in museums. And she’s right—it is a shame that a museum isn’t permanently exhibiting local artists.