Phoenikera Artist Celebrates Every Thread of Her Indigenous Fiber

She’s a jeweler, not the kind who wears a loupe at a store or sits in a dark room inside a diamond and gemstone warehouse. She makes earrings, bracelets, and necklaces that reflect her connection to her ancestors. She designs her pieces considering what they would wear as adornments.

She’s also pursuing a fiber arts degree.

Through her art, she celebrates her ancestry and identity. Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

While she sips a cup of joe, she expresses that art is a blessing, a divine energy, and it excites her to learn different techniques from our ancestors, what they created for us, and the identity it gave us, the sense of belonging.

In process… Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

“Their work made an impact. It sent a loud message: we are here, we are important,” she says, wild-eyed and with a spark that’s fueled every time she talks about art.

I ordered a Sessions, but the server can’t copy my pronouciation. I crank it up so she gets it, but I end up sounding like a cheesy actor doing a mediocre British accent.

We resume our fiber arts conversation (she lights up again), and she tells me about the manual labor involved and the manipulation of fiber materials. She also explains that it is an ancient process practiced by many cultures worldwide and is deeply communal.

This prietita is in love with who she is and her Indigenous fire! Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

She appreciates the influence of fibers on clothing and jewelry and the historical value of weaving as one of the oldest art forms. Dyes are also part of the chat; she tells me a story about a classmate who dyed cotton using plants and bugs, as many ancient civilizations did.

Her interest expanded to experimentation with mixed media, which has helped her regain confidence. She even calls herself an artist because, as she says, it takes guts to do that. “When you call yourself an artist, you put yourself out there, all your beliefs and all who you are for people to see and judge,” she says.

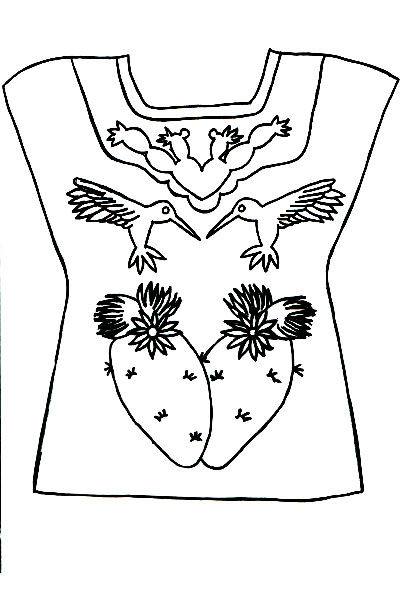

She’s a jewelry maker at heart but is experimenting with multiple mediums. Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

She laughs at how shitty she thought her sketches were, and now, with some guidance, she’s producing stuff she’s proud of.

This is not one of the shitty sketches. Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

For a second, I get distracted by the light entering from a nearby window, brightening her eyes like two mirrors and bouncing it off onto me. When I snap out of it, she’s talking about the moment of “the unknown,” that instant when she’s about to create something, when she’s in that energy of making and wants to get lost in it forever.

The arts weren’t part of her life growing up in León, Guanajuato, or even when she migrated to the U.S. at 8 years old with her mom, grandma, two older brothers, a younger sister, and a cousin.

I’m mesmerized by her story about a seal, blue-lit by the full moon and dead on the beach while on her path to the border; about the two times it took for them to cross and effectively stay on this side; about tip-toeing the shallow water of the Rio Grande River all the way to shore, and then making it to the city with just a plastic bag; about being stared up and down on the bus because they were dirty from the journey.

…Now she gets dirty with paint. Photo: Alonso Parra/Lamp Left Media.

It was the first time she felt unwanted. “As an immigrant, you constantly feel unwanted, especially now,” she says. When she tells me these details, I feel sadness, but I also feel joy.

She laughs the way people do when admitting a guilty pleasure and says her first bought cassette was Christian Castro’s, and also is a hardcore fan of La Trevi, Alejandra Guzmán, and Timbiriche.

We don’t know if this is the cassette, but we sure do love the cover!

Their first encounter with art was near her house on Tamarisk St. on the South Side when she saw local artist Martin Moreno painting a mural. She lights up once again.

She took the time to let me know about her photography classes in 7th grade and later in high school, her first fiber class during the same academic years, where she discovered jewelry-making and her love for it.

“It takes guts to call yourself an artist.” She’s one gutsy gal! Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

She hopscotched through the South Side with her family and graduated from South Mountain High School. Her hard work as a student created plenty of options for her future. She went on to become a nurse with a scholarship but couldn’t get her license because she was undocumented.

The unwanted feeling she’s always had hit her like a punch in the gut. Inevitably, she also remembers being picked on because she was a few shades darker, the “prietita” people would call her, and because of it, she suppressed her Indigenous side.

What people used to otherize her, she now uses as strength. Photo: Gloria Casillas-Martinez.

Gloria Casillas-Martinez says that now she’s reclaiming who she is; she now understands that the side people otherized is precisely the one that gives her the feel, the spark.

Gloria became an artist when she wasn’t allowed to practice nursing. When things were rough, she saw how Kathy Cano-Murillo, la Crafty Chica, had a lot of success selling her crafts. She decided to sell her crafts, too, and joined The Phoenix Fridas. Art was a way to channel energy, making her feel good about herself.

She can’t hide her excitement about the possibilities. Her craft and the new venture into fiber arts complement each other, and no doubt a new era awaits.

Gloria is also psyched about her new show with three other La Phoenikera artists, which will open on September 2nd at The Sagrado Gallery in South Phoenix. The show unifies the voices of artists with similar experiences as undocumented immigrants, creative beings, and women of color.

She’s hella fired up about collaborating with Gio (Áviles), Chela (Meraz), and Carla (Chavarría). To tell their story and allow herself to communicate and have a dialogue about the real impact of policies upon communities.

We can’t wait for this to happen already!

For Gloria, it takes people like her, who are targeted on multiple fronts, to be involved in the project and use art as a platform to show others how affects her life. She tells me the artist’s job is to point the finger and be conscious of what you put out there because of how it affects society, and this show is part of that.

The server asked us for the twelfth time if we were okay; she seemed annoyed by us. We’ve been too wrapped up in our roles (I try to keep up with Gloria’s anecdotes). I want to ask a few more questions before the server returns with hot oil and pours it over our faces.

She tells me her favorite place in La Phoenikera is South Mountain, which connects her to her place. “No matter where you leav” town, when you come back and see those lights at the top of the mountain, you know you’re home,” she says wiyou’reull sm”le.

Gloria is pointing fingers with her art. Photo: Alonso Parra/Lamp Left Media

La Olmeca is her favorite place to eat, and she doesn’t really connect with the term “SoPho”, which she thinks takes away from what the place is. She thinks SoHo is bougie.

As enjoyable on that steamy day marching towards 4th Ave. jail, at The Sagrado Gallery when we discussed the future of the South Side, or at a downtown eatery finding out what she’s about, talking to Gshe’s is never empty, never hollow, never inconsequent. Hopefully, you will hear her experiences firsthand at the show on 9/2.

The exhibit starts at 6:00 p.m. at The Sagrado Gallery on 6437 S. Central Ave.