Afromexico: Children of the moon

Queen Muhammad Ali and Hakeem Khaaliq, two local visual anthropologists, have made it their mission to demystify preconceived notions about black and Indigenous communities worldwide.

This is no easy feat since they’re against a historical propensity to spread inaccurate information about communities of color (at this point, we’re all misinformed about everybody else, really), erase or undermine their cultural relevance and contributions to humanity. In our good ol’ AZ, we even banned the study of said groups. But they have two powerful tools: art and technology.

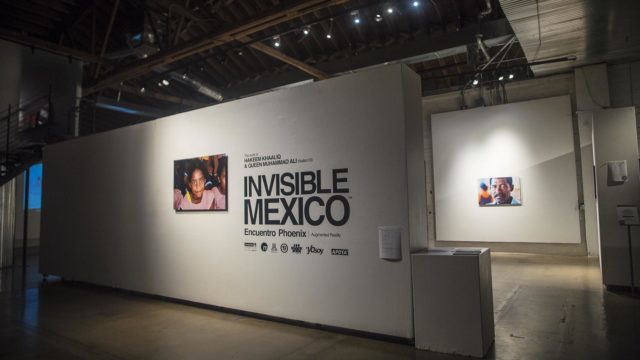

A few days ago, I walked down Roosevelt after getting some grub at one of the eateries. Inside MonOrchid was a fantastic photograph of a girl’s face, a giant print of one of the most piercing eyes I’ve ever seen… a future Bruja, if you will. These eyes have a story, a history. I went in. Invisible Mexico was the exhibit’s title, and to its creators, it’s an anthropological portrait of the African Diaspora of settlers in Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Chiapas, Michoacán, and other Mexican states.

A crowd was already hurdled around the artists, so it was almost inappropriate not to eavesdrop on their narration. It wasn’t just an explanation; they had some techie stuff—augmented reality—which blew my mind immediately.

My thoughts exactly when I saw the first picture. Photo credit: Jimaral Marshall.

Queen and Hakeem have been traveling to Mexico since the 1990s for different projects (some we can mention, others not so much). They’ve traveled to too many places to list, even on this slim paragraph. However, it is important to mention that their voyages have taken them to places with large Afro-Mexican communities, which are sadly unknown.

Hakeem, originally from South Central L.A. and Queen from L.A. (her ancestry is American Samoan royalty), would tell an anecdote behind the picture, where it was taken, and the context. With their tablet, they would create an interactive environment that immediately connects with the audience, establishing a learning space for everyone.

Attendees get mind-blown with the experience! Photo credit: Jimaral Marshall

The actual explanation of augmented reality is complex. Still, for this article, we’ll synthesize by saying that when you hold your mobile device over one of the photographs, the pictures become animated and provide further information about the image hanging on the wall. This is ain’t magic stuff, though ancient curanderos would freak the F out! This augmented reality experience is a collaboration between Queen, Hakeem, the University of Arizona, and Associate Professor Bryan Carter. This effort produced an app for mobile devices that could expand a gallery’s experience to a much broader space, immersing the audience into a different kind of reality: the subjects’ realm.

But beyond the augmentation of an experience, its bidimensional reality has a unique depth, and behind the photographs displayed, there is a history that has been ignored for a minute or two. I was confronted with my ignorance about Afromexican communities in Mexico and here in the U.S. (there’s a large population of Afromexicans in Califas, as depicted in this awesome short).

Hakeem says it is rare for Afromexicans to be photographed because they consider themselves ugly. Photo credit: Hakeem Khaaliq

Hakeem explained the history behind Yanga (Nyanga or Gaspar Yanga), a man from the state of Veracruz whose photograph hangs on a wall of the exhibit. He awoke a whole town and led them to resist their oppressors. The sound of his name resonated with me; then it hit me. There’s a region in Bolivia, Los Yungas, in La Paz. I’m Bolivian, and my heart has a special place for Saya, a dope Afrobolivian beat. So naturally, when he said his name, I was curious. There has to be some connection, especially when this Andean tropical forest extends from northern Peru and Argentina, passing through Bolivia and up to Colombia and Venezuela.

What is known about Yanga is that he was apprehended somewhere in the Brong-Ahafo region of Ghana and disembarked on the coast of Veracruz in the 1500s. He was briefly enslaved until he escaped and lead a 30-year crusade against the Spaniards…¡toma! He was the first great liberator of the Americas. Way before El Libertador did his thing in South America, Nyanga sealed a treaty with the Spaniards that would allow freemen to live in a sovereign, Gachupin-free land in the early 1600s. Also, the meaning of Nyanga will blow your mind, but I’ll come back to that in a bit.

Nyanga, the first Libertador in the Americas. Photo credit: Hakeem Khaaliq

Queen and Hakeem were really impressed with his story, but they also realized that many African descendants felt a void in their roots and history, that there wasn’t an accurate representation of them.

“If we don’t change these stories and people’s perceptions, no one will,” Said Hakeem.

That is why they’ve put up this show, a collection of photographs made over a decade of travels through Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tepoztlán, and Costa Chica. Queen explains how these communities’ perception of themselves has affected their collective self-worth in respect to other Mexicans. I mean, it wasn’t until an internal census in 2015 that Afro-Mexicans had a box to self-identify. Up until then, they didn’t have a box to check. This is precisely why there isn’t knowledge of the prevalence of African cultures settled in Mexico because everything was focused on Indigenous people or mestizos. Also, Afro-Mexicans aren’t even considered a minority because, according to the government, they don’t have a native language or dialect. As a consequence, their history has vanished.

Some Mexican archaeological sites have shown the presence of African descendants. Photo credit: Hakeem Khaaliq.

The good thing is that there is a new-found pride in being Afro-American, and now they can identify with their blackness and own it like the woman in this short documentary. Also, visual artists and anthropologists constantly travel to these regions, and others in the Americas where there are large populations of African descendants, and their stories aren’t represented.

Queen and Hakeem’s Invisible Mexico will be at MonOrchid, 214 E Roosevelt St., until this First Friday, 4/7. Check out the space, approach the artists, and ask them questions. They’re awesome at sharing knowledge and have a truly keen eye for stories.

Now, are you ready to learn the meaning of Nyanga? Well, the short answer is witch-doctor, but it’s too generic and whitewashed. Now, Occult Zulu has an interesting interpretation, and we kind of like it better. It basically means moon-ritual-person. It turns out that some plants’ properties react to the lunar cycles, and in ancient Africa, there were special humans who knew when to conduct rituals based on this to increase effectiveness. These special people were viewed as saviors, and they called them Nyanga.

You can pay a visit, check out the exhibit, and feel a little less ignorant about the world you live in. In this case, ignorance is not bliss; it is a sin. Also, check out this jam—it’s pretty awesome!