Chela Makes Art Because It Doesn’t Ask For Papers

Much of what Isela Meraz has done in the U.S. has been to challenge a system that requires her to show papers. Art is one of those things. In 2014, though, art became more of a tool for self-preservation. That’s when she started drawing in the sketchbook, which she says saved her life.

She showed me the sketchbook in her studio, a space she always wanted to have but didn’t think she could.

“I always dreamed of having a space to do my art, but I had to think about money. Now I have DACA, and I can work, but before, everything was more uncertain,” she says, expressing her gratitude to La Muñeca, a Phoenikera artist who invited her to share the studio with another artist.

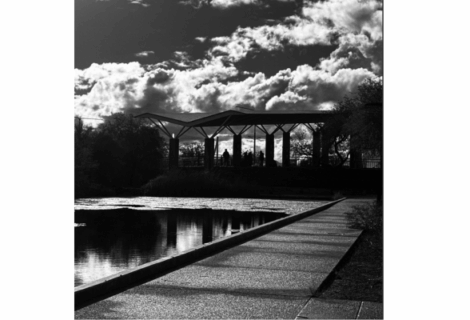

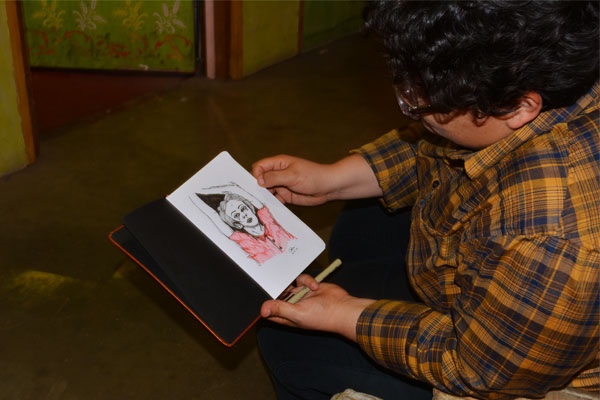

Chela shows the first drawing she made in her sketchbook. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com

Chela (as her friends call her) came to the U.S. when she was 8. She crossed through El Paso with her mom, dad, brother, and sister. They stayed in El Chuco for a few days, then made their way to La Phoenikera. They landed on the West Side at her grandmother’s house.

She started going to Cartwright School, and she remembers drawing the illustrations from the Ramona book series. For her book reports, she’d draw the main character and write a little bit about the book, but when she presented that in class, they teased her because they thought she traced them. “That would bother me so much, and I would tell them, ‘No, I didn’t trace them!’ but they didn’t believe I knew how to draw.”

She learned more about art when she was around 10 years old from her art teacher, who had a mustache like Salvador Dalí’s.

Self-portrait with Dalí mustache.

At home, Chela’s interaction with art was through lowrider magazines. There were always stacks of them at her house because her uncle would bring them over. “People submitted drawings, and they published them. Those were the best, and the work was so beautiful!” Those magazines are the reason she uses Old English letters (AKA cholo letters) in some of her artwork now.

I met Chela back in the mid-2000s, but not as an artist. I knew her as a badass music promoter in La Phoenikera. She had a company called Mundo Rojo Entertainment and was bringing bands to the city that fed the musical cravings of rockeros and fans of independent music. Bands like Zoe, El Gran Silencio (the band members stuffed their faces with Chela’s mom’s gorditas de azúcar), and Panteón Rococó. I met her when her hair reached her shoulders, and it would fling side to side when she indulged on the dance floor.

Chela in front of one of the portraits she’s preparing for her show on Sept. 2. Photo by Chela.

I didn’t know then that she brought those bands to our city. Yes, she did so to contribute to the music scene, but mainly because she loved those bands and couldn’t go down to Mexico to see them live. Funny all the things a border fucks with.

For some time, Chela felt like she hadn’t accomplished anything. This person who other promoters looked up to didn’t feel like the events she organized, the talent she brought, and the music she introduced us to amounted to much. Mind you, she is responsible for taking the Phoenikra band Babaluca to L.A. for the first time, where they gained popularity. Babaluca’s lead singer at the time is now Grammy award-winner Carla Morrison.

Chela with Vira Lata, a former L.A. band Los Abandoned member and current El Conjunto Nueva Ola member. Photo by Chela.

These defeatist thoughts roamed Chela’s mind in 2012. She had been active in the Undocumented and Unafraid movement and had recently returned from riding the Undocubus.

Immigration raids were raging in the city, she had applied for DACA but it was denied and her mom said to her “don’t get a job. The raids are happening right now, and your DACA was denied. I don’t want something to happen to you, and they deny it again.” She was in a rough place for a couple of years.

In 2014, many years after her childhood depictions of Ramona, she started drawing on a sketchbook she bought once when her mom sent her to Michael’s to get crafting supplies. “My mom sent me to the store with 20 bucks, and when I saw that the sketchbooks were on sale for $7, I thought, ‘I hope my mom doesn’t ask me for the change because I’m gonna spend the rest of the money on this.’”

Chela posts her drawings on her Instagram account @chelinski.art.

That’s the sketchbook that saved her life. It served as a catharsis for what she calls her undocudepression. Every time she thought about something negative, she turned to art. “I found some comfort. It started teaching me things that nothing else around me was teaching me.” Chela is an entirely self-taught artist.

She started drawing every night. She looked for pictures on Tumblr and saved them on her phone for later projects. Then she started drawing people, something she had avoided when she used to delve into acrylics (Oh yeah, as a kid, she saw Bob Ross and wanted to paint like him…we all did!). “The way I was looking at things changed completely, not emotionally but with my eyes,” she says. “I was looking at someone and could already see myself drawing them. Like, I see you now, and I already know your face…I see the lines.”

Portrait of Julia Duran, one of the women Chela will feature at her show (see it completed on Sept. 2). Photo by Chela.

To Chela’s surprise, the same year she started drawing, a friend who owns Espacio 1839, a gallery in L.A., asked her to have a show at their place. Chela didn’t think he cared for her art because he hadn’t “given it a little heart on Instagram.”

“I took three or four weeks to answer, hoping that it would be too late and they no longer wanted me,” she says, laughing. “At the time, my work was personal. I made it when I was super sad, and now people would see it.”

They still wanted her, though. In 2015, Chela had her first solo show in L.A., which was special. She went all out. She printed t-shirts because she got a great deal from Sam Gomez (Phoenician Clothing and The Sagrado Galleria). She had prints and gave stickers to everyone who went up to talk to her during the show.

The crowd at her L.A. exhibit at Espacio 1839. Photo by Marco Loera.

Chela wanted for everyone who walked into the gallery to be able to leave with something. She thought about people like her, who might be undocumented and unable to work but might have five bucks in their pocket.

“To me, that was very important because, for us, the kids from the hood who dream of studios and having our art displayed somewhere, art has not been something we’ve been able to possess. It has been something that has saved us from ourselves.”

Since then, Chela’s also had a sold-out solo show here in La Phoenikera at Abe Zucca Gallery and made illustrations for the book Nómada Temporal by Luis Ávila. Now she’s preparing pieces to be part of a show called “Las fronteras nos dividen, pero el arte nos une” with four other Phoenikera artists (Gloria Martinez-Casillas, Giovana Aviles, and Carla Chavarría) on September 2. The event will start at 6 p.m. at The Sagrado Gallery on 6437 S. Central Ave.

Chela created the image for their event flyer featuring drawings of all four artists. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com

She’ll be featuring portraits of six women. “They’ve played a big role in my life as a person who keeps growing, loving, and understanding my queerness. It is with them that I’ve always been able to see myself just as I am.”

Chela’s hair no longer reaches her shoulders, and it no longer covers her face when she dances, although she still takes all of us out to dance when we’re at the same party. She also no longer feels unaccomplished; she feels like an artist. “I feel really good. I feel like it’s very me.”