Anna Flores’ Pocha Theory is a Book You Must Own

A few weeks ago, I ran into an event on Facebook: The release of Pocha Theory by Anna Flores at the Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center (ALAC). I thought it looked interesting and I clicked “going.” Then I thought, “Here we go again, more mariachis, more ballet folklórico, more ‘my abuelita’ here, ‘La Virgen de Guadalupe’ there.”

When the event day came, I showed up at ALAC with my hopes lingering around my toes.

I went in, greeted the author, purchased the book (you have to purchase the book!) and made my way to the seating area. I couldn’t find a seat. ALAC was filled and not with the usual suspects. It was a gathering of people of color: Brown, Black, Native. It was an intersection of generations: high schoolers, college students, old school artists parents of teenagers.

Dozens of people gathered at ALAC for Anna’s release of Pocha Theory. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com.

Anna’s stage reading was preceded by Enrique García Navarro, a young writer from Tucson and Nova Baze from La Phoenikera.

Then, Anna went on stage wearing a yellow and patterned outfit. Over it, a sheer coat of young power. She opened with Pocha.

No soy de aquí.

No soy de allá.

Yo soy todo lo que hay allí.

Yo soy todo lo que hay aquí.

Yo soy el de-aquí-pa-allá.

Yo soy el de allá-pa-qa.

Estoy aquí cuando se supone que debo estar allá.

Estoy allí cuando se supone que debo estar aquí.

Solo estoy allá para venir aquí.

Solo estoy aquí para ir allí.

Anna sold out the first edition of her book the night of her release. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com.

Anna proceeded to read more poems, though not too many. “I won’t give them all to you for free” she said. Each bundle of verses she read felt more crude, more ambivalent, more real. The hairs in the back of my neck gave her a standing ovation a couple of times.

I became interested.

Then, she explained why she called the book Pocha Theory: “Every other little brown girl isn’t deemed with enough time and space to call themselves a genius. Nobody ever thought that we were self-aware because we were so hell-bent on surviving. But we have theories too.”

OH MAI GA! Holly baby Jesus and his brown mother Tonantzin. I could only imagine the sense of validation that statement gave to all the “little brown girls” in the audience.

Lastly, as if to stick a dull knife in our guts she finished by reading Mexicans Are Such Hard Workers, which ended like this:

At home, the men pluck their eyes out while they eat.

The world would end if we saw them cry.

Mexicans are such hard workers.

Mexicans are such

hard workers.

Mexicans are workers.

Mexicans work.

Mexican, work!

Work, Mexican, Work!

Mexicans are such hard workers.

They say it like it’s an honor

To watch my father die.

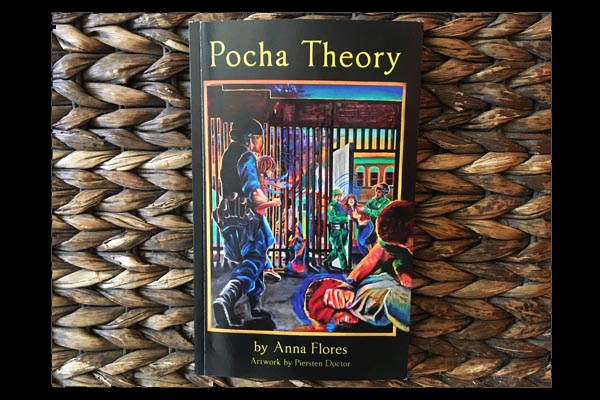

Pocha Theory’s front cover was designed by Piersten Doctor. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com.

Contrary to what I thought when I clicked “going” on her facebook event, Anna showed to be a strong writer, eloquent, congruent, powerful.

See, at 22 years old Anna is a thinker, a person who questions the role she plays in this world, a player who is figuring out how to make the best game with the cards she was dealt.

She is disciplined, a hard worker. She gets up at 6 a.m. to write, holds three jobs and just finished her last semester at ASU with a bachelor’s degree in English.

When she was five years old, she understood she was poor because during Christmas time, a truck full of toys showed up at her apartment complex and all the toys were for her and her siblings. She thought “we must be really poor if are the ones getting this.” Her five-year-old mind compelled her to ask her mom if the toys were from Santa Claus to make her mother feel a little better.

When she started writing at 6 a.m. every day, she understood that as an ASU student she had adapted to the privilege of going to college. “Something about that made me less tolerant because I became uppity; I became too good for the things that I’d already known.”

Anna’s family at her ASU graduation. From left to right, Anna’s nieces Paola and Emily Flores, her sister-in-law Elvira Leal and her parents Norma Acosta and Feliciano Flores. Photo courtesy of Anna Flores.

When she began writing Pocha Theory, she questioned some of her mentors who told her she should say things in a way that is more abstract to be less heavy.

“I’m not supposed to say ‘This country is a rave in the desert where white people wear headdresses.’ I’m supposed to write in a way that is celebrating who I am and write shit like ‘my brown skin is the color of the mountains and my grandmother’s flowers bloom out of my ears.’ But that’s not true; I don’t feel any of that.”

Anna started writing Pocha Theory in 2017. However, the process that made her land on the book as it is written now started about two years ago when she realized she had a lot of poems written and she should probably do something with them.

The first title of her book was Good Girls Don’t Die and she says it was a “self-glorification anthology.” She was writing about feeling suicidal in middle school. She wrote about boys and about not feeling pretty.

It wasn’t until she started developing the book and writing every day that she dug deeper into what her poems were really about. “The one constant in all the poems was a feeling of loneliness, a feeling of utter helplessness,” she says.

Anna Flores and collaborating artist Piersten Doctor. Photo by LaPhoenikera.com.

Anna is a U.S. citizen. She is part of what is called a mixed-status family, which the National Immigration Law Center (NILC) defines as “a family whose members include people with different citizenship or immigration statuses.” In Anna’s case, she lives here with her mom, a citizen, her dad, a non-citizen and two brothers, one is a citizen, the other holds a work permit. One of her brothers lives in Nogales.

In Pocha Theory, Anna writes about her constant frustration with the border. “The border is what created all this imbalance in my life. It was why we were poor; it was why we were alone and why my brothers weren’t with us. It was why my family fought,” she explains.

The latest manifestation of the border’s effect in her life was the fact that her book release was almost canceled. Her brother tried to cross the border days before to be reunited with his two daughters. He couldn’t do it and was detained in Eloy, waiting to be deported.

“I thought, I can’t do the book release. How am I gonna go and pretend everything is all good?” she says. In the end, she decided to move forward with the event, and it turned out to be something good for her family.

Even though Anna writes about the border and her experience being a brown woman in the U.S., the themes she explores and the perspective she offers are new.

“I read Gloria Anzaldúa and Sandra Cisneros and I love their work, but it’s not our story. The stories of my peers, who went to Pueblo del Sol and Carl Hayden with me and were very confused when SB1070 happened…when we saw our families and our friends move back to Mexico, it’s a completely different narrative,” she explains.

In 2017, Anna played the lead role in James Garcia’s play SB1070.

In Pocha Theory, Anna is refreshingly truthful and raw; she is unapologetically political and intends to stay on that path despite the advice some of her mentors. She is critical of those who push her to write in a way that doesn’t reflect her experience.

“I can’t romanticize SB1070 by saying ‘the grey piece of paper that floated…’ No. The name was SB1070. I can’t follow Bradbury’s Rules for Writers. There’s no rule for it, no literary tool for saying that the border wall has ruined so many of our lives.”

The book includes poems about love like First Loves Make you Hate Your Mom, about trivial moments like Joshua Drumming at the Lunch Box and about Womanhood like In God’s Sculpture Glass.

Not all the poems are about the border. However, they all have the border looming over them. That is the genius of Pocha Theory. The writing is not tired; it is not black or white but black and white.

For Anna, it was just as important to include the pieces that were quieter about the wall than to include the loud ones. “Because that’s what it is to live in a mixed-status family,” she says. “You overwhelmingly live in this very heavy and tense space but have moments when you can say ‘I want go to prom tonight,’ or ‘I’m going to go to the museum.’ We do things that are not acted upon with the fear of the border in the back of my head.”

Anna collaborates with artist friends on different projects. Here she is photographed by Jairo Carreón. Photo courtesy of Jairo Carreón of Creative Collective Productions.

Anna Flores is an educated woman both by her circumstances and academia. She doesn’t read acclaimed contemporary authors as much as she reads Joel Salcido, Rashaad Thomas, Megan Atencia, Amanda Astrid and other writers from La Phoenikera.

She released Pocha Theory at a public event because she believes brown writers deserve the dignity of putting out a book that people can hold, and reading it in front of an audience.

She is thinking of going to law school to be able to help her family but it would be a huge loss for the sphere of writers in our city.

Pocha Theory is a proud product of La Phoenikera, and we think you should read it. You can get it at ALAC located at 147 E. Adams Street and online at Barnes & Noble.